Palazzo Barberini

Overview

The Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Antica at Palazzo Barberini in Rome is a treasure trove of art from the 13th to the 18th centuries. Housed in a stunning Baroque palace designed by Carlo Maderno, Gian Lorenzo Bernini, and Francesco Borromini, the gallery showcases masterpieces by artists like Caravaggio, Raphael, and Titian. Originally the Barberini family's residence, it became a national museum in 1953. The collection includes over 4,000 works, offering a chronological journey through Italy's artistic heritage.

IMPORTANT UPDATE:

From March - July 2025 Palazzo Barberini will be hosting a Caravaggio Exhibit featuring at least 16 additional Caravaggio paintings:

Saint Catherine of Alexandria

Martha and Mary Magdalene

Saint John the Baptist in the Wilderness

Saint Francis of Assisi in Ecstasy

The Cardsharps

The Martyrdom of Saint Ursula

Portrait of Maffeo Barberini as an apostolic protonotary

Portrait of Antonio Martelli

Supper at Emmaus (Milan version)

Boy Peeling Fruit (Royal Collection)

Flagellation of Christ

David with the Head of Goliath (Borghese)

Conversion of St. Paul (Odescalchi)

The Musicians

The Taking of Christ

Ecce Homo (Prado)

As such, the location of the Caravaggios mentioned in the itinerary may be incorrect as they will probably be moved during the exhibit. We will keep this itinerary as updated as possible.

https://barberinicorsini.org/en/caravaggio-2025/

Before you go

Check the website for the times that the gallery is open

Definitely purchase tickets ahead of time if you are going during the Caravaggio Exhibition.

Itinerary

Entrance

The first floor of the gallery contains only medieval pieces, which are interesting but if you are short on time you can skip it and go straight to the second floor. If you have your tickets already, you can go directly to the second floor(1st Piano) and do not need to stop into the ticketing area.

The entrance is accessible off of the street and you can walk up the driveway and veer left to find the main archway just past the fountain. If you want to go to the second floor, turn left immediately past the first set of arches and you will see signs for the stairs and second floor (1st piano) of the gallery. If you are heading to the ticketing area / medieval paintings, do not turn after the arches, keep walking straight and follow signs that lead to the entrance to the gallery on the left.

As you reach the top of the stairs you will see a very cool veiled statue named “Veiled Woman” (1743) by Antonio Corradini. Turn to the right and show your ticket at the door and you will begin our itinerary. Turn left and follow the signs to Raphael. The first two pieces are bonus pieces, from the renaissance.

Bonus Works

La fornarina (c. 1518) Raphael

“La fornarina” (c. 1518) by Raphael has recently been restored and is stunning. There is much speculation as to the identity of the woman, it could be a girlfriend, his representation of beauty or his representation of a prostitute. The woman’s expression appears to be slightly amused and she doesn’t appear to be embarrassed or shy about her state of undress.

Henry VIII (1540) Hans Holbein The Younger

“Henry VIII” (1540) by Hans Holbein The Younger shows the king before his 4th marriage. The marriage to Anne of Cleves might not have lasted long, but this portrait still looks amazing, the detail of the fabric and jewels is stunning.

After you are done with Henry VIII, walk through four more rooms and turn to the right. You will see Baglione’s masterpiece on the far right wall.

Sacred and Profane Love (1602) Baglione

Sacred and Profane Love (1602) by Giovanni Baglione is his most famous painting and subject of much debate. This is the first time Baglione had attempted to mimic Caravaggio’s naturalism and use of light in a painting. It is thought that the painting is a direct response to Caravaggio’s painting “Love Conquers All,” which depicts Cupid standing upon many earthly things. In Baglione’s painting, Caravaggio’s cupid is seen meeting with the devil when they are interrupted by “Sacred Love.” This painting is the second version of the subject by Baglione. The first version does not show the Devil’s face. Caravaggio accused Baglione of plagiarism when he saw the first version of the painting as he felt it copied his own style too closely. Baglione was teased and insulted by Caravaggio’s circle and painted a second version of the painting which shows the Devil’s face with Caravaggio’s features and Cupid with similar features as Caravaggio’s model.

To the right of Baglione is Vouet’s take on Caravaggio’s Fortune Teller.

The Good Fortune Vouet (1620)

“The Good Fortune” by Simon Vouet is his take on Caravaggio’s masterpiece. Vouet takes a different approach on the subject and shows us a rather rustic young man who is convinced to have his palm read by a fetching fortune teller without noticing the trap he is about to fall into. The naive young man is more attracted by the gypsy woman's seductive gaze than by her fortune telling abilities. The viewer is made an accomplice by the crone behind him, uncouthly making the vulgar gesture of the so-called "fig sign", which needs no explanation and alludes to the fact that this unsuspecting man has just had his money bag stolen.

Before you exit the room, check out one more piece on your left.

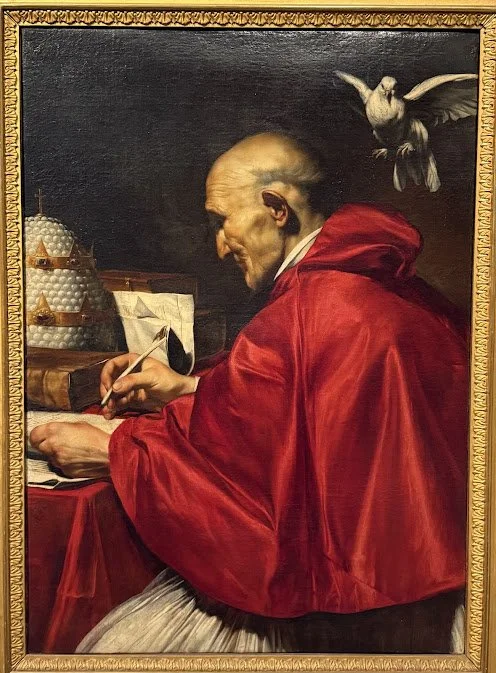

St. Gregory the Great (c.1614) Ribera

“St. Gregory the Great” (c1614) by Spagnoletto (Jusepe de Ribera) shows realistic textures, especially in the silky mozzetta of the pope, who almost has his back to us and turns his ear towards the viewer. This isn't a random choice. According to tradition, St. Gregory wrote his works by secretly listening to the Holy Spirit, which appears here as a dove behind the saint's shoulders. Only we can see this miracle of divine inspiration happening.

Walking into the next room you will find Narcissus towards the end of the room on the left.

Narcissus (c.1597) Caravaggio

“Narcissus”(c.1597) by Caravaggio. We see Narcissus leaning forward and fully enraptured by his own reflection in the pool. His left hand is already in the water, in an attempt to allow himself to lean even further forward. The composition of this painting is extremely unique, with the mirror image pivoting on Narcissus’ extended knee. The provenance of this painting is not well documented and has come into question by a few scholars, but most agree that only Caravaggio could have conceived and executed such a unique image.

After admiring Narcissus, look to the right and you will see two images of St. Francis, we will start with the right most image by Orazio Gentileschi.

St. Francis and the Angel (c. 1615) Gentileschi

"St. Francis and the Angel” (c. 1615) by Orazio Gentileschi feels like it's meant for deep thinking and spiritual growth. Instead of showing St. Francis in a state of ecstasy, he's depicted reliving Jesus' suffering. His collapse looks a lot like paintings of Jesus' agony in the Garden of Gethsemane, where, since the late 16th century, Jesus is often shown almost unconscious and being supported by an angel. St. Francis' stigmata and his painful imitation of Jesus are also shown very physically on his body.

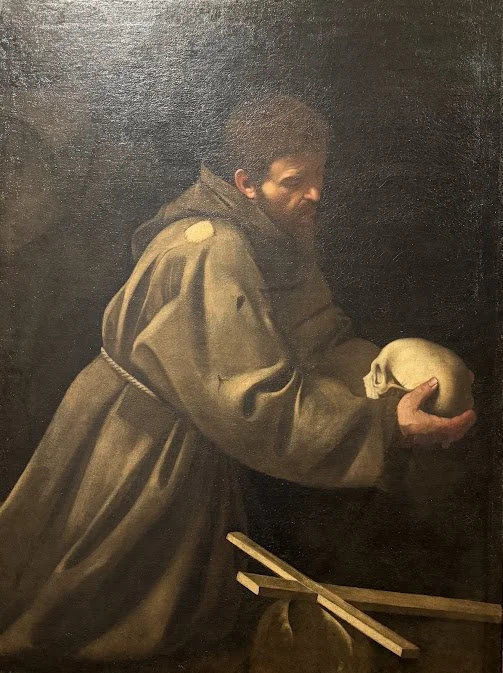

St. Francis in Meditation (c.1606) Caravaggio

"St. Francis in Meditation (c.1606) by Caravaggio shows the saint all alone, with nothing around but the stone the cross rests on. St. Francis is kneeling and looking at the skull he's holding, almost as if he's caressing it. This is a typical Caravaggio touch, related to imitating Jesus. It hints at Christ praying in front of the chalice in the Garden of Gethsemane. Instead of the chalice, a symbol of Christ's human suffering, there's the skull here – a stark reminder of mortality. This connection highlights the bond between Jesus and Francis, the first man in Christian history to bear the stigmata; the same wounds as the crucified Christ.

Walk to the left of these paintings and enter another room and you will see Caravaggio’s St. John immediately on the left.

St. John the Baptist (c 1604) Caravaggio

“St. John the Baptist” (c 1604) by Caravaggio. St. John takes center stage in this painting, shaped by light. The contrast between his arms and legs, along with the twist of his shoulders and face, emphasizes his dynamic pose. His gaze, partly shadowed, looks far into the distance, almost predicting the future. Caravaggio depicts St. John in the desert, focusing on the moment he awakes from his sleep and realizes his future mission as a preacher. The bare landscape includes symbolic objects like the bowl, the cross of canes he's leaning on, the stones, and the hollow trunk in the background. These objects highlight the mere beginnings of St. John’s journey and have yet to achieve their future symbolic meaning and hint at his prophetic destiny.

Opposite of St. John is Caravaggio’s masterpiece and one of the BAAC’s favorite paintings.

Judith and Holofernes (c.1598) Caravaggio

“Judith and Holofernes”(c.1598) by Caravaggio is bloody, graphic and sexually charged. This sets the tone for future Baroque artists- a near obsession with depicting death in motion. The old maid next to Judith serves to emphasize Judith’s seductive charms and her expression of “it must be done” counters Judith’s expression of uncertainty.

In the next room over from the Caravaggio’s you will find Preti’s masterpiece.

The Escape from Troy (c.1640) Preti

“The Escape from Troy”(c.1640) by Matia Preti catches the eye immediately with the interesting depiction of the Escape from Troy. Preti on several occasions tried his hand at painting characters and moral themes from ancient history. Here the protagonist is Aeneas, a solemn example of pietas, respectful of men and of the wishes of the gods. As Virgil tells us in the Aereid, he saved his elderly father Anchises from the city of Troy, visible in the dark background, set ablaze by the Achaears. His wife Creusa, on the right, is looking backwards, an omen of her tragic fate: she will be lost during their escape. Strangely, his son Ascanius is ahead of the group, while in Virgil's text he follows his father on the right side. This may be because Ascanius’s descendants will begin the city of Rome and Ascanius is emulating his father’s pose, showing that young Ascanius will go on to great things.

Mary Magdalene (c.1626) Cagnacci.

“Mary Magdalene”(c.1626) by Guido Cagnacci. Cagnacci clearly had a thing for painting seductive female figures. His take on Magdalene fits into a long tradition of depicting her life. After seeking refuge in a cave in Provence, she gives up worldly pleasures and lives as a hermit. Next to her, there's a cross, the pot of spikenard she used to anoint Christ's feet at the supper in Bethany, and in her hands, a skull and a scourge which she uses for self-mortification. Despite whether her 'swoon' is mystical ecstasy or the effect of asceticism, the painter suggests a gaze that doesn't seem to be marked by severe penance; similarly, her body shows no signs of mortification.

Exit the room and you can walk to the far left corner to see Caravaggio’s portrait of Maffeo Barberini.

Portrait of Maffeo Barberini (c.1598) Caravaggio.

“Portrait of Maffeo Barberini” (c.1598) by Caravaggio. This is a portrait of the future Pope Urban VIII and the man who commissioned the building the Palazzo Barberini in 1623. The quality of the painting is magnificent and even at the young age of 30 you can see Barberini’s leadership qualities expressed so clearly in the painting.

Enter the large Ballroom on your way out of the Gallery

The Triumph of Divine Providence … (1639) Cortona

The Triumph of Divine Providence and the Fulfilment of íts Purposes under Pope Urban VIII - Pietro da Cortona and his team painted this fresco between 1632 and 1639. It’s a massive celebration of the Barberini family’s spiritual and political power, featuring over a hundred characters in an infinite open space. The only thing that grounds your view is a big, rectangular frame painted to look like marble, dividing the vault into five sections.

At the center, Divine Providence sits on clouds, holding a scepter and instructing Fame to crown the Barberini coat of arms. Each of the side panels shows contrasting ideas like vices versus virtues, good versus evil. You’ve got Minerva taking down Giants, Theology and Religion fighting off lechery and debauchery, Hercules driving away the greedy Harpies, and Good Government banishing war and ensuring peace. With its dynamic energy, fast-paced rhythm, and impressive spatial illusion, this fresco is one of the earliest and most amazing examples of Baroque painting.

This concludes our quick tour of the Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Antica at Palazzo Barberini.